Enthalpy of fusion

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The enthalpy of fusion (symbol: ΔfusH), also known as the heat of fusion or specific melting heat, is the amount of thermal energy which must be absorbed or evolved for 1 mole of a substance to change states from a solid to a liquid or vice versa. It is also called the latent heat of fusion or the enthalpy change of fusion, and the temperature at which it occurs is called the melting point.

When you withdraw thermal energy from a liquid or solid, the temperature falls. When you add heat energy the temperature rises. However, at the transition point between solid and liquid (the melting point), extra energy is required (the heat of fusion). To go from liquid to solid, the molecules of a substance must become more ordered. For them to maintain the order of a solid, extra heat must be withdrawn. In the other direction, to create the disorder from the solid crystal to liquid, extra heat must be added.

The heat of fusion can be observed if you measure the temperature of water as it freezes. If you plunge a closed container of room temperature water into a very cold environment (say −20 °C), you will see the temperature fall steadily until it drops just below the freezing point (0 °C). The temperature then rebounds and holds steady while the water crystallizes. Once completely frozen, the temperature will fall steadily again.

The temperature stops falling at (or just below) the freezing point due to the heat of fusion. The energy of the heat of fusion must be withdrawn (the liquid must turn to solid) before the temperature can continue to fall.

The units of heat of fusion are usually expressed as:

- joules per mole (the SI units)

- calories per gram (old metric units now little used, except for a different, larger calorie used in nutritional contexts)

- British thermal units per pound or Btu per pound-mole

- Note: These are not the calories found in food. The calories found in food are more properly known as kilocalories—equal to 1000 calories. 1000 calories = 1 kilocalorie = 1 food calorie. Food calories are sometimes abbreviated as kcal as if small calories were being used, while calories are abbreviated as cal. Another distinguishing method, though often confusing, uses capitalisation. A Calorie is a food calorie, or 1000 calories. So 1 Cal = 1000 cal.

Contents

|

[edit] Reference Values of Common Substances

| Substance | Heat of fusion (cal/g) | Heat of fusion (kJ/kg) |

|---|---|---|

| water | 79.72 | 333.55 |

| methane | 13.96 | 58.41 |

| ethane | 22.73 | 95.10 |

| propane | 19.11 | 79.96 |

| methanol | 23.70 | 99.16 |

| ethanol | 26.05 | 108.99 |

| glycerol | 47.95 | 200.62 |

| formic acid | 66.05 | 276.35 |

| acetic acid | 45.91 | 192.09 |

| acetone | 23.42 | 97.99 |

| benzene | 30.45 | 127.40 |

| myristic acid | 47.49 | 198.70 |

| palmitic acid | 39.18 | 163.93 |

| stearic acid | 47.54 | 198.91 |

These values are from the CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, 62nd edition. The conversion between cal/g and kJ/kg in the above table uses the thermochemical calorie (calth) = 4.184 Joules rather than the International Steam Table calorie (calINT) = 4.1868 Joules.

[edit] Applications

To heat one kilogram (about 1 litre) of water from 10 °C to 30 °C requires 20 kcal.

However, to melt ice and raise the resulting water temperature 20 °C requires extra energy. To heat ice from 0 °C to water at 20 °C requires:

- (1) 80 Cal/g (heat of fusion of ice) = 80 kcal for 1 kg

- PLUS

- (2) 1 cal/(g·°C) = 20 kcal for 1 kg to go up 20 °C

- = 100 kcal

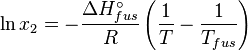

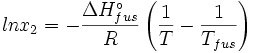

[edit] Solubility prediction

The heat of fusion can also be used to predict solubility for solids in liquids. Provided an ideal solution is obtained the mole fraction of solute at saturation is a function of the heat of fusion, the melting point of the solid and the temperature of the solution:

For example the solubility of paracetamol in water at 298 K is predicted to be:

This equals to a solubility in grams per liter of:

which is a deviation from the real solubility (240 g/L) of 11%. This error can be reduced when an additional heat capacity parameter is taken into account [1]

[edit] Proof

At equilibrium the chemical potentials for the pure solvent and pure solid are identical:

or

with  the gas constant and

the gas constant and  the temperature.

the temperature.

Rearranging gives:

and since

the heat of fusion being the difference in chemical potential between the pure liquid and the pure solid, it follows that

Application of the Gibbs-Helmholtz equation:

ultimately gives:

or:

and with integration:

the end result is obtained: